- Technical Manual

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Theory and Background

- Chapter 3: Administration and Scoring

- Chapter 4: Scores and Interpretation

- Chapter 5: Case Studies

- Overview

- Case Study 1: Clinical Evaluation of an English Speaker Suspected of Having a Speech-Language Impairment

- Case Study 2: Progress Monitoring of an English Learner with Suspected Deficits in Verbal Ability and Language

- Case Study 3: Psychoeducational Evaluation of an English Learner with Suspected Specific Learning Disability

- Chapter 6: Development

- Chapter 7: Standardization

- Chapter 8: Test Standards: Reliability, Validity, and Fairness

- Task Instructions Scripts

Interpretation of Ortiz PVAT Scores |

This section provides a recommended six-step framework for interpreting the Ortiz PVAT. Examination of the scores begins with establishing context, which may include checking notes from the administration or becoming familiar with the examinee’s background. Next, the scores should be thoughtfully interpreted, and results regarding instructional needs, recommendations for further vocabulary growth or intervention, and details about performance regarding different elements of vocabulary should all be reviewed. Results can also be compared over time to assess growth or progress. The following recommendations are guidelines that should be considered when interpreting results from the Ortiz PVAT.

Step-by-Step Interpretation Guidelines

- Step 1: Establish Context and Determine Validity

- Step 2: Interpret the Scores

- Step 3: Review Instructional Needs & Intervention Recommendations

- Step 4: Examine Performance by Vocabulary Type

- Step 5: Evaluate Change Over Time

- Step 6: Report Results

Step 1: Establish Context and Determine Validity

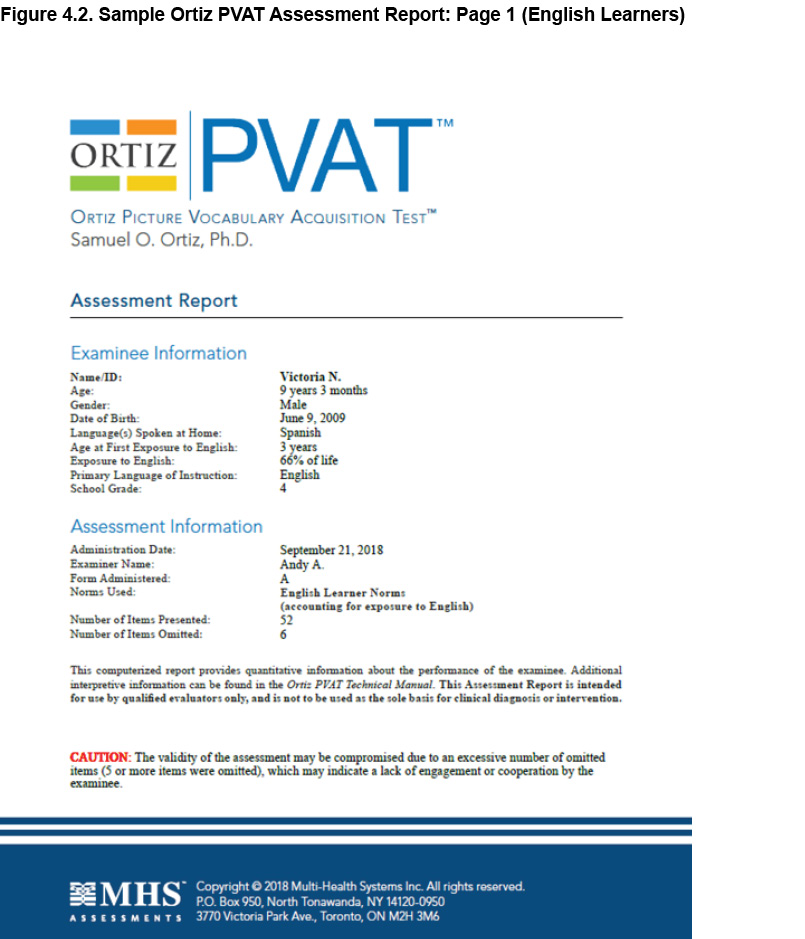

The first step in interpreting Ortiz PVAT results is to examine administration information and the examinee’s details provided on the cover page of the Assessment Report. A sample cover page is presented in Figure 4.2. Make note of the examinee’s age (and for English learners, their lifetime exposure to English). To validate that the correct report was produced, confirm the form administered (Form A or Form B). Ensure that the proper scoring methodology was applied by confirming the norm used for scoring (i.e., English Speaker norms or English Learner norms). The norm used to score the examinee’s test is determined by the response provided to the language-related demographic questions during the assessment (or prior to generation of the report, if the information was not available at the time of testing), which identifies the examinee as either an English speaker or an English learner (see Step 2: Complete Client Information in chapter 3, Administration and Scoring, for more details).

The number of items presented, along with the number of items omitted (i.e., skipped), can be used as a potential indicator of attentiveness and engagement. An unusually low number of items attempted during an administration could have resulted from a variety of reasons that include carelessness or intentional incorrect responding that inadvertently ended the test. Likewise, there could be any number of reasons why an individual may choose to omit an item (e.g., hesitant to take a guess, disengaged from the task, or acting uncooperatively). A few omitted items are unlikely to greatly influence scores on the assessment. However, omitted items are scored as incorrect. If more than five items in a series of ten items are omitted, the examinee would reach the ceiling and the test would be terminated. By omitting too many items, the examinee may reach an artificial ceiling that does not accurately reflect their ability. In other words, it is possible that they could have continued the assessment had they attempted those omitted items.

When more than five items are omitted on the test, a warning will appear at the bottom of the cover page of the report (as seen in Figure 4.2). The warning cautions that the validity of the reported scores may be compromised as a result of omitted items. For example, the obtained raw score may be lower than what could have been obtained had the items not been omitted. This underestimated raw score, in turn, affects the standard score; in other words, the obtained standard score may not accurately reflect the examinee’s vocabulary acquisition. Alternatively, omitted items could indicate inattention during administration, such that none of the responses provided are representative of the examinee’s true performance. The choice to omit a large number of items may be important qualitative information. Check examiner notes with regard to attentiveness, comprehension of the task, and potential of malingering, or ask the examinee about their experience during the test.

Step 2: Interpret the Scores

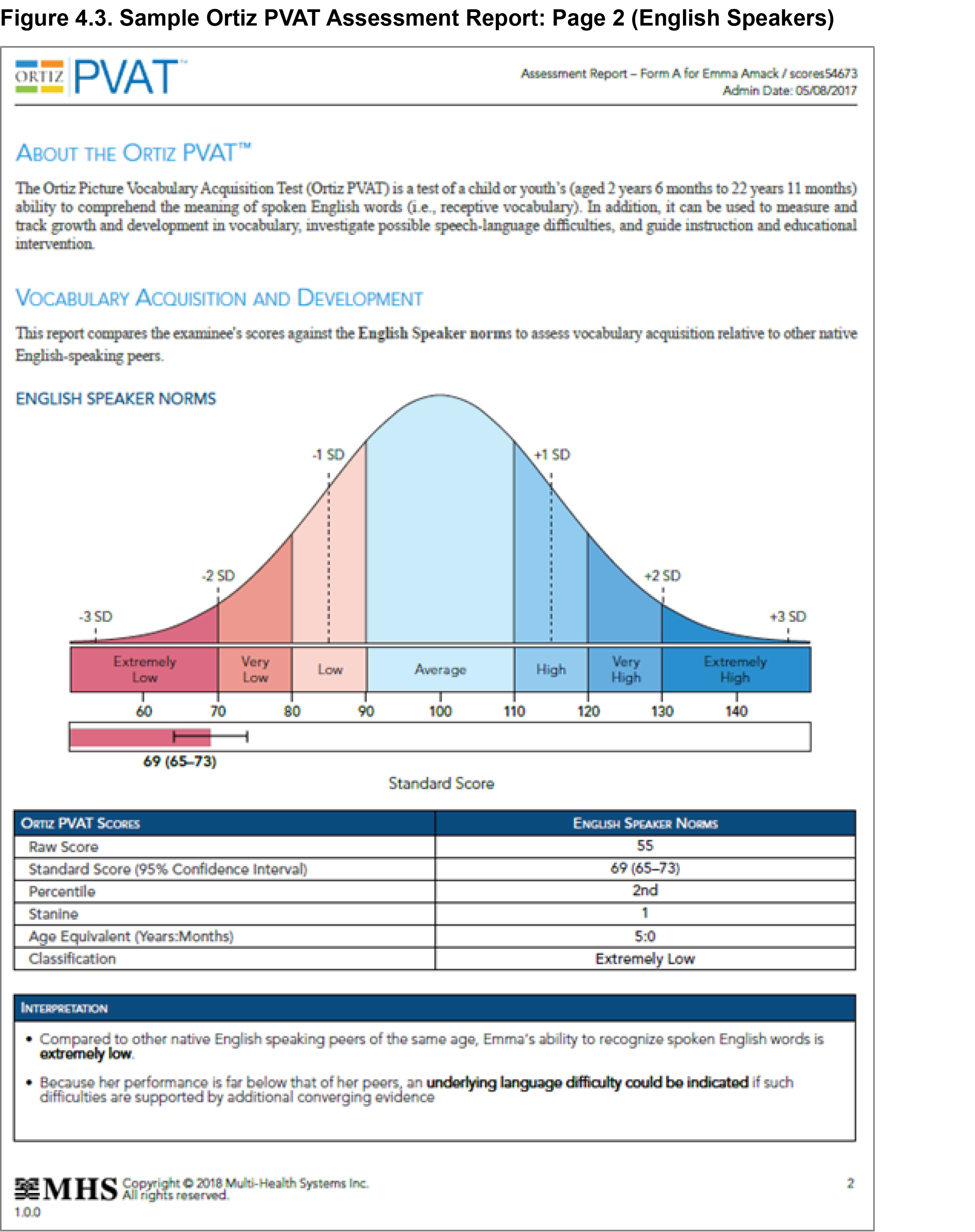

The second step of interpreting the Ortiz PVAT results involves examining the reported scores, their classifications, and the interpretative information provided in the Ortiz PVAT Assessment Report (see the Vocabulary Acquisition and Development section of the report; sample provided in Figure 4.3). Review the following results, which are presented at the top of the report page, and evaluate their significance:

- The raw score conveys the number of items answered correctly (including correct responses to the Screener items for which they also received credit).

- The standard score, percentile rank, and stanine all provide information about the individual’s relative performance.

- For English speakers, receptive vocabulary acquisition is compared to other same-age monolingual native English speakers.

- For English learners, individual performance is compared to other English learners of the same age who have been exposed to English for the same proportion of their lifetime.

- The age equivalent score communicates the age typically associated with the individual’s raw score.

- For English learners, the age equivalent score also accounts for the individual’s length of exposure to English when identifying the age most typical of a given raw score.

Special Topic: The Importance of English Learner Norms and Controlling for English Exposure for English LearnersAs discussed in chapter 2, Theory and Background, it is important to recognize that English learners begin the process of learning English at different ages. As such, it is necessary to account for English learners’ inherent variability in English exposure if norms are to provide a fair and “true peer” standard for comparison. Only in this way can a valid determination be made about whether a lower performance in English vocabulary is attributable to the normal process of learning another language (due to limited exposure to English) or an intrinsic language difficulty. Although comparison of an English learner’s performance to age-matched native English speakers is inherently discriminatory when attempting to ascribe cause to low scores, such comparisons do provide a valid baseline measure of an English learner's current English vocabulary acquisition relative to same-age peers. Although it is inappropriate to use such comparisons for diagnostic purposes, it can be used to identify an English learner's current instructional level and need for intervention and assistance. Even when controlling for English exposure, it is possible that children and youth may differ in significant ways with respect to their actual English exposure. Thus, it is always best practice to consider to what extent the presence of certain factors (e.g., native-language education, parents’ ability to support English literacy, socioeconomic status, and exposure to English within the community) assist in deriving valid inferences and drawing defensible conclusions from the scores generated with the Ortiz PVAT. |

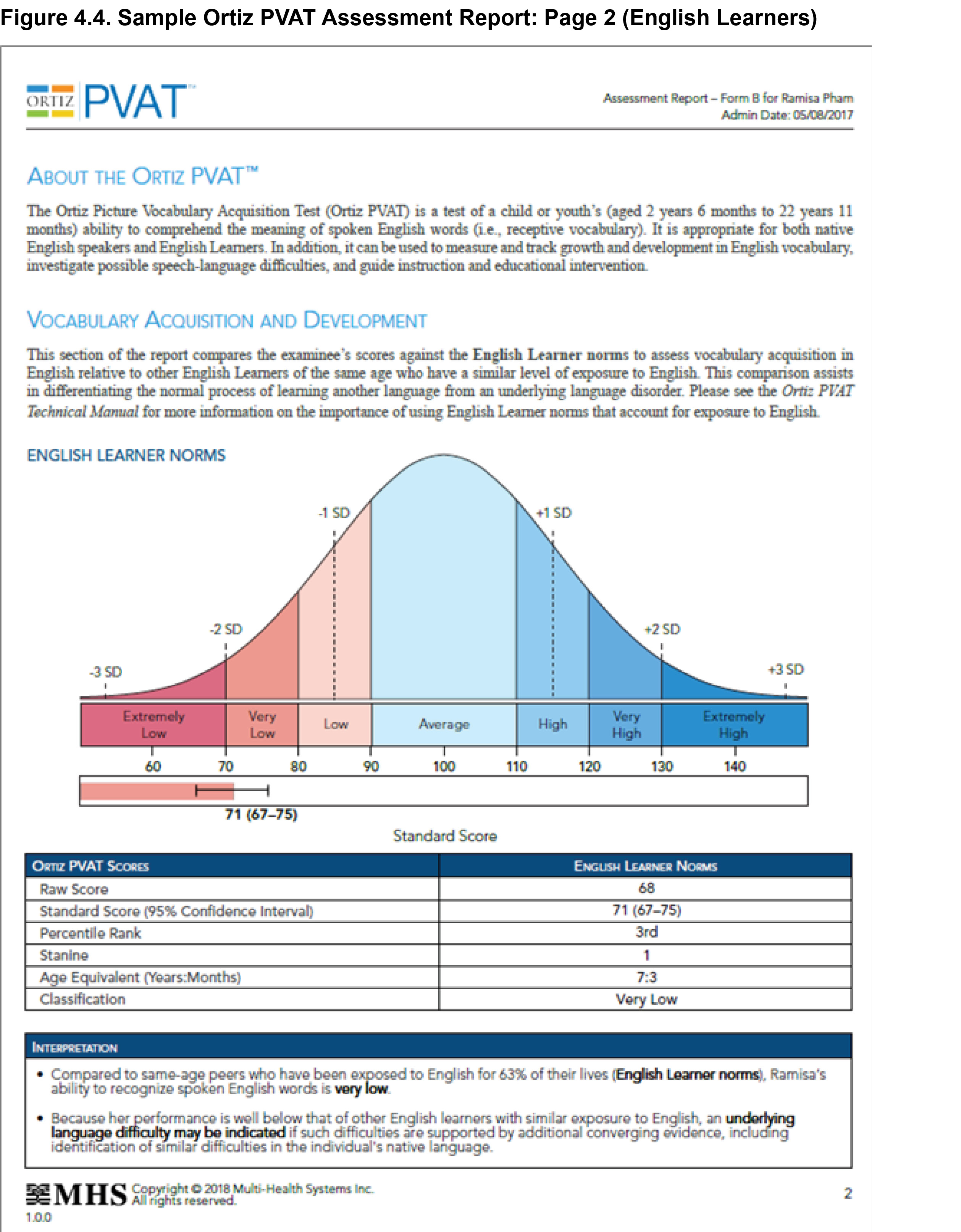

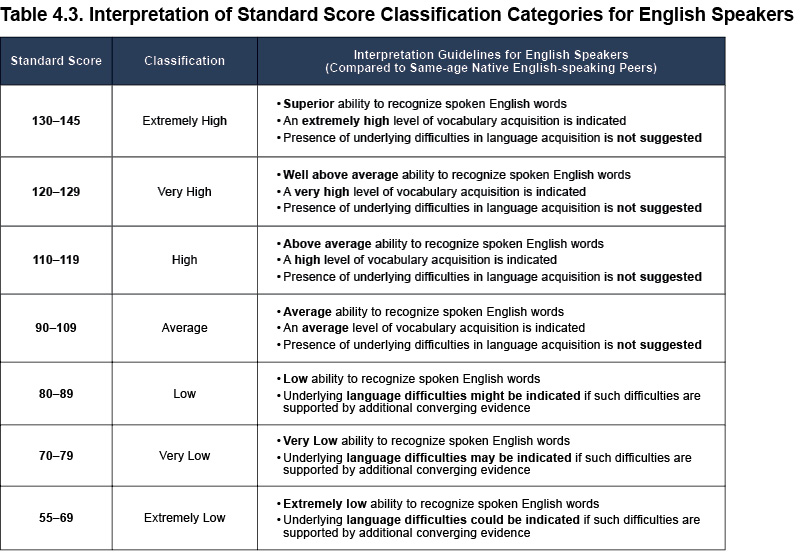

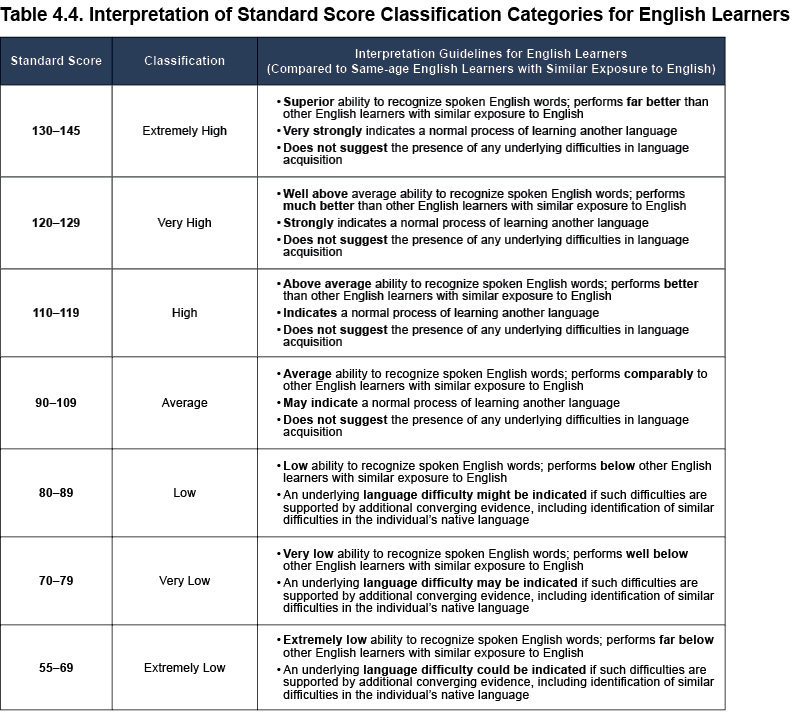

When analyzed together, the scores describe the current level of the examinee’s receptive vocabulary acquisition. Higher scores on the Ortiz PVAT represent higher levels of vocabulary acquisition compared to peers of the same age, or of the same age and exposure to English for English learners. Scores are classified into descriptive categories to aid interpretation. Interpretive text is provided in the table at the bottom of the page to summarize the examinee’s obtained results (see Figure 4.3 for a sample page from the Assessment Report for an examinee who was compared to the English Speaker normative sample, and see Figure 4.4 for an assessment scored using the English Learner norms). Table 4.3 presents the interpretive guidelines for English speakers and Table 4.4 presents this information for English learners.

Step 3: Review Instructional Needs & Intervention Recommendations

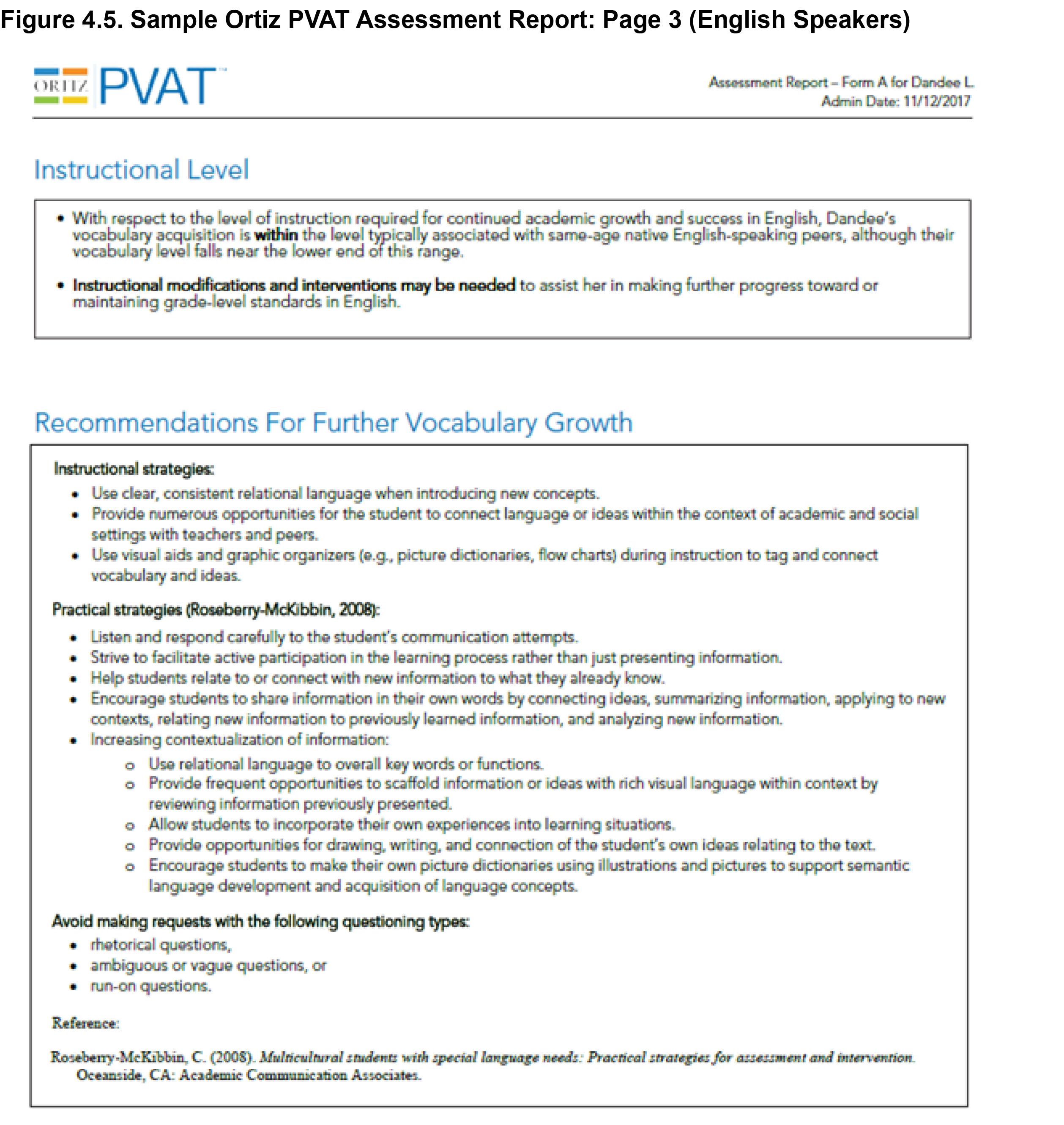

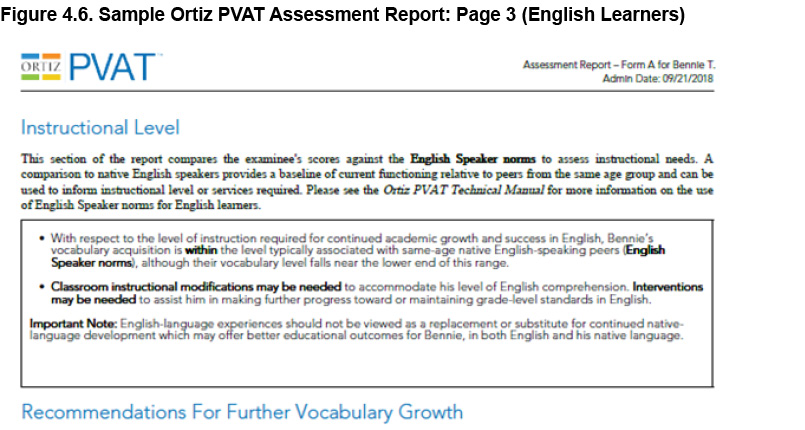

The third step in the interpretation of results from the Ortiz PVAT is to inspect the Instructional Level section of the report (as seen in the sample Assessment Report in Figure 4.5). Alternatively, this section is called Early English Learning Experiences for examinees between the ages of 2 years 6 months and 5 years who have not yet begun school, or English Learning Experiences for examinees older than 6 years of age who are not currently enrolled in school. Based on the results from this section, determine whether their English-learning experiences have been sufficient, or if interventions are necessary to promote continued and further development of English vocabulary. As mentioned in Special Topic: The Importance of English Learner Norms and Controlling for English Exposure for English Learners, results from this section of the report are derived from standard scores in comparison to other native English speakers, regardless of whether the examinee is a native English speaker or an English learner. Note that standard scores between 90 and 95 are identified as falling at the low end of the Average range. For scores in this range, consider the need for instructional modifications and interventions, which can assist the examinee in making progress toward or maintaining grade-level standards in English.

In addition, consult the Recommendations for Further Vocabulary Growth section (also shown in the sample Assessment Report in Figure 4.5; the same section is named Intervention Recommendations in instances where standard scores are Below Average). For English speakers and English learners alike, recommendations are determined based on standard scores as compared to other same-age English-speaking peers. However, recommendations on reports for English learners were written to provide specific intervention and further development suggestions with English learners in particular. Together, these two report sections provide action-oriented feedback with regard to the examinee’s test scores.

English Speakers

Intervention and instruction, regardless of the examinee’s level of vocabulary acquisition, should include specific and appropriate language-related feedback and correction. If the examinee’s level of vocabulary acquisition is within the level typically associated with same-age native English-speaking peers, their English-language interactions have likely been sufficient to allow development of an average level of vocabulary. For individuals at this level who are enrolled in school, instructional modifications and interventions would not be needed to make further progress toward maintaining grade-level standards in English.

Similarly, if the examinee’s level of vocabulary acquisition is above the level typically associated with their native English-speaking peers, their English-language interactions have been sufficient to promote an above-average level of vocabulary. Instructional modifications and interventions are very unlikely to be required.

Nevertheless, when the examinee’s current vocabulary level is either within or above the level typically associated with same-age native English-speaking peers, the following activities may assist in developing even higher levels of vocabulary (Brown & Ortiz, 2014):

- explicit instruction in the use of language

- continued vocabulary development in all content areas (e.g., sciences, humanities)

- opportunities to practice more complex grammatical forms of language

- explicit instruction in more subtle details of English usage and rule exceptions

- introduction to concepts of metaphorical language and text

- introduction to advanced forms of figurative language and grammar in instruction

- assignment of rigorous grade-level readings that may include classic texts

- opportunities for engaging in verbal debates and rhetoric to learn how to justify and defend opinions or ideas

- use of advanced forms of idiomatic language and grammar in instruction

- opportunities for advanced linguistic analysis and synthesis

On the other hand, if the examinee’s level of vocabulary acquisition is below the level typically associated with same-age English-speaking peers, interventions are necessary to promote further development of English vocabulary. In terms of instructional needs, modifications are needed to assist the individual in understanding materials taught in the classroom. Examples of instructional modifications and intervention strategies may include (Brown & Ortiz, 2014):

- frequent and multiple repetition of communication vocabulary

- use of short, simple sentences

- opportunities for language practice with partners

- instructional use of visual materials and realia (e.g., objects, pictures, illustrations)

- extensive and repeated language modeling

- continuous checking for understanding and comprehension

- use of word banks

- recognition of synonyms and antonyms

- identification and focus on addressing gaps in knowledge of the English language

English Learners

As mentioned earlier, while the section on Vocabulary Acquisition and Development in the Assessment Report displays scores for an individual as compared to other English learners of the same age and exposure to English, the Instructional Needs section (also known as the Early English Learning Experiences section for younger examinees who are not in school yet [ages 2 years 6 months to 5 years 11 months], or the English Learning Experiences section for examinees over the age of 6 years who are not currently enrolled in school), instead, compares the individual to native English speakers of the same age (see Figure 4.6). Although this comparison is not appropriate for diagnostic and disability identification, it is suitable for examining an English learner’s English-learning experiences and their current instructional level needs or educational services required for optimal academic performance. A comparison of the individual to native English-speaking peers provides a valid baseline of current functioning relative to peers from the same age and language group and provides insight into their capabilities relative to grade-level expectations (if currently enrolled in school). For individuals not currently enrolled in school, interpretation of this section pertains to general English-language learning opportunities (e.g., English-language interactions) to continue developing English vocabulary.

For English learners whose level of vocabulary acquisition is comparable to, or above, the level typically associated with same-age native English-speaking peers, classroom instructional modifications are not needed to accommodate them in making further progress toward or maintaining grade-level standards in English. For those who are not in school yet and whose English-language interactions have been sufficient to promote an average or greater level of vocabulary acquisition, sustaining English-language interactions may help foster even higher levels of English vocabulary. Accordingly, the same strategies recommended for native English speakers will also help English learners attain even higher levels of vocabulary development.

In contrast, English learners with a Below Average level of vocabulary acquisition (when compared to same-age native English-speaking peers) may require substantial modifications to English instruction to accommodate their level of comprehension, depending on their current level of English vocabulary acquisition. For example, intensive interventions may be necessary to promote further English vocabulary development in individuals whose current acquisition is below what is typically expected of others of the same age or grade. In addition to the strategies mentioned in the previous section for English speakers with a Below Average level of English vocabulary, the following list provides additional recommendations that are more specific to English learners in terms of instructional modifications and intervention strategies (adapted from Brown & Ortiz, 2014; Sanford, Brown, & Turner, 2012):

- further develop vocabulary by building upon existing cultural and linguistic knowledge and experiences

- provide visual support for vocabulary (e.g., use of pictures, illustrations, gestures)

- pre-teach content vocabulary (i.e., introduce some of the more difficult words in a chapter within a book prior to teaching the chapter’s content)

- use simple, high frequency phrases

- link to prior knowledge (may include knowledge gained from native language)

- create opportunities for authentic, everyday life scenarios to practice and develop better fluency and automaticity in communication (e.g., role-playing telephone conversations or making purchases at a store)

- promote and reinforce English-language use outside of the classroom

Step 4: Examine Performance by Vocabulary Type

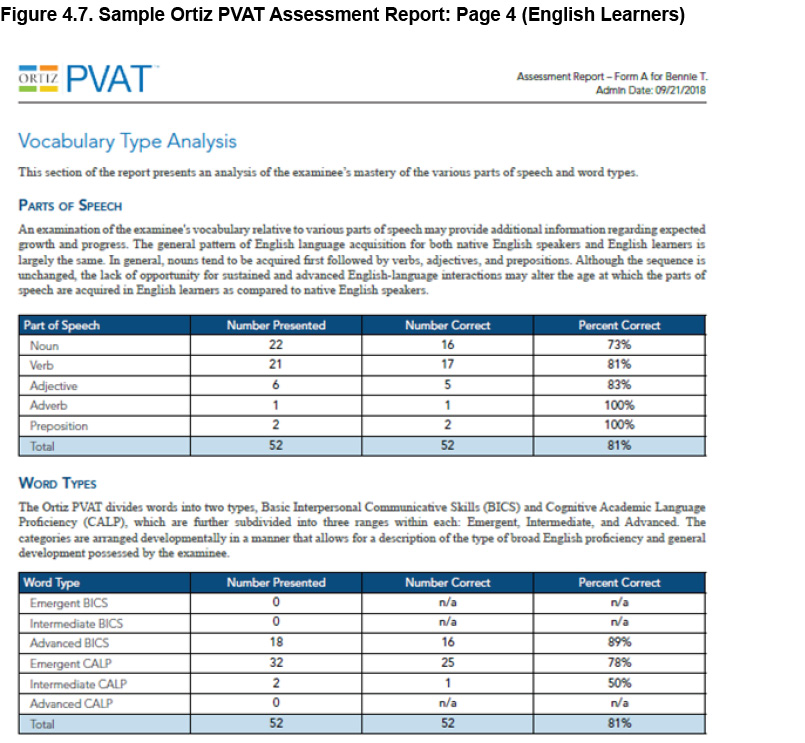

An analysis of an individual’s performance by vocabulary type represents the next step in the interpretation of Ortiz PVAT results. This analysis relies on information found in the Vocabulary Type Analysis section (see Figure 4.7 for a sample). The individual’s mastery of different parts of speech (i.e., nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and prepositions) and different types of words (i.e., Emergent Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills [BICS], Intermediate BICS, Advanced BICS, Emergent Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency [CALP], Intermediate CALP, and Advanced CALP) are described in terms of the number of items presented, the number of items answered correctly, and the proportion of correct responses by each vocabulary type.

With respect to parts of speech, the general pattern of English vocabulary acquisition for both native English speakers and English learners is largely invariant (Terrell, 1984). In general, nouns tend to be acquired first, followed by verbs. Prepositions are usually learned incidentally via everyday conversations. Adjectives and adverbs are the last parts of speech to be mastered since they are more subsidiary parts of speech used to describe nouns and verbs, and all of these parts of speech are acquired in relation to word frequency (i.e., higher frequency precedes lower frequency words). Due to challenges in aptly depicting movement with two-dimensional images, as well as the stringent item selection criteria as described in the Analysis of Standardization Study Data section of chapter 6, Development, there is a limited number of adverbs and prepositions on each form. Even though information regarding an examinee’s performance on a small number of items would not be definitive or diagnostic when considered in isolation, such information still provides nuanced insight about the examinee’s English language acquisition. This information might be useful for diagnostic decision-making and developing recommendations for intervention or instruction, in conjunction with other pertinent information about the examinee’s language use. For example, an examiner may decide that more adverbs and prepositions should be explicitly taught, alongside other parts of speech. Moreover, comprehension of nouns, verbs, and adjectives may be more advantageous than knowing adverbs (which are used to describe actions) in order to understand written text or conversations in social or academic settings. Nouns and verbs, at both the BICS and CALP levels, appear more frequently in text and conversations. One might even argue that it is more important for a test of English vocabulary to place a higher emphasis on these parts of speech that tend to be acquired first, rather than words that are used to describe objects, people, and actions. As long as an examinee understands the verb used in a sentence, it is possible to decode how the action is performed using contextual cues provided within the sentence or passage. Even when such cues are unavailable or not helpful, comprehension of the general sentiment is unlikely to be greatly impacted.

Although the sequence of acquiring parts of speech is unchanged for English speakers and learners, the lack of opportunity for sustained and advanced English-language interactions may delay the age at which English learners acquire different parts of speech compared to native English speakers. Careful consideration of these results in relation to parts of speech may illuminate areas in need of improvement and can guide education planning.

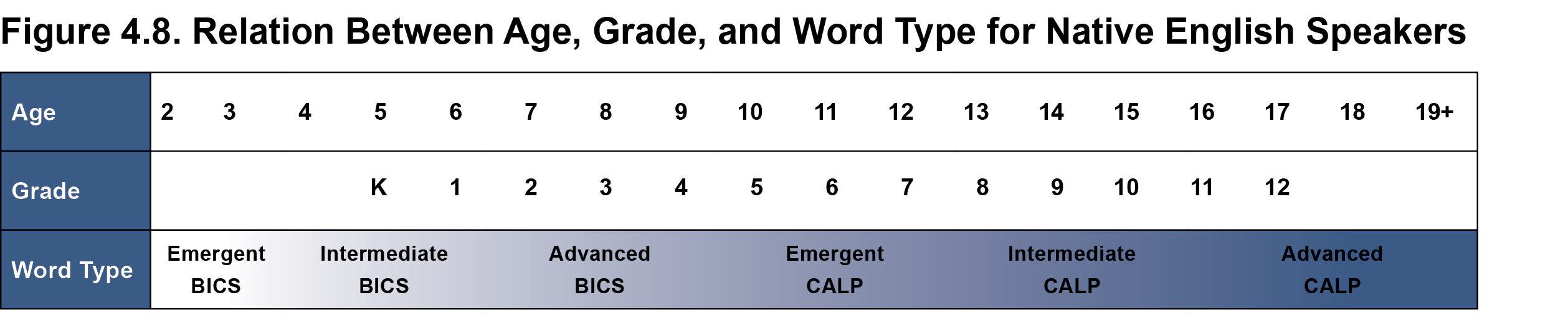

Next, examine the Word Types table that categorizes words into BICS and CALP, both of which are further subdivided into three linear ranges: Emergent, Intermediate, and Advanced. The categories are arranged hierarchically to reflect the individual’s general English-language development. Analysis of the degree of BICS and CALP word acquisition may inform an individual's current instructional needs by indicating whether or not expected grade-level proficiency has been attained, and to what extent. For example, proficiency at the CALP level is expected to emerge around 4th grade. Thus, if a 3rd grade examinee identifies words correctly in the Emergent CALP range, they may be seen as slightly ahead of expectations. In contrast, a 5th grade examinee who achieves the same proficiency would be either slightly behind or close to what is expected for their grade level. In addition, because BICS level words reflect conversational language and speaking ability, an inability to make adequate progress in the acquisition of these types of words would suggest a broader degree of difficulty in general language acquisition. Conversely, because CALP-level words reflect more academic and formal language, an inability to progress in the acquisition of these types of words would suggest specific difficulty in school-based learning. Neither condition necessarily reflects an intrinsic deficit, however, because factors such as simple disinterest in content reading, limited opportunity for incidental learning experiences, and lack of age-appropriate language models outside of school could all influence acquisition of both word types.

A visual representation of the theoretical progression of vocabulary type is presented in Figure 4.8. For native English speakers, word types tend to be acquired in a linear fashion, progressing sequentially as age and grade progress. Figure 4.8 also depicts the notion that early conversational language development and concomitant vocabulary acquisition proceeds more rapidly earlier in the learning sequence than later on. That is, the acquisition of CALP words (substantially more numerous than BICS words) is deliberate; these words are acquired primarily through formal instruction, incidental reading, or conversation with individuals who have a high vocabulary level, whereas BICS words are gained in quick succession through regular conversation and everyday social interaction. Unless one pursues higher education, vocabulary acquisition tends to plateau after high school due to the abrupt lack of structured exposure to increasingly advanced vocabulary words. However, the linear relationship (depicted in Figure 4.8) is suitable only for expectations of vocabulary acquisition in native English speakers, because it is presumed that the process of learning the English language begins at birth and typically progresses in a predictable fashion. For an English learner or an individual who learns English and another language at birth, the development of vocabulary is, by definition, not tied necessarily to age or grade. The English learner can begin their development at any point along the age or grade continuum. For example, most native English-speaking 4-year-olds are likely to know Emergent BICS words as they are just beginning to learn the language (i.e., their native language, L1). However, a 17-year-old English learner could also be at the Emergent BICS stage of development, as they are also just beginning to learn the English language (i.e., their non-native language, L2). Although this stage may be behind what is typical of other native English-speaking 17-year-olds (or perhaps even behind other 17-year-olds who are English learners but have more exposure to English), it becomes imperative to consider the length of exposure to English. Regardless of exposure to English, comparisons to this development trend can be useful in identifying whether true progress is being made.

As indicated by Figure 4.8, the progression from BICS to CALP (moving through the three subcategories of each word type) is linear, such that the categories are ordered sequentially throughout the Ortiz PVAT (i.e., for both test forms, Test Item 1 is classified as Emergent BICS, and Test Item 167 is classified as Advanced CALP). Understanding the examinee’s performance by word type can help inform specific instructional needs and intervention planning.

Analysis of these item-level results can be used to identify areas in need of improvement and directs attention to specific parts of speech and types of words that are most appropriate for the examinee’s level of vocabulary. Moreover, instructional modifications may involve adjusting instructed content to accommodate the parts of speech and types of words (e.g., emphasis on common nouns and verbs, as opposed to less frequent adjectives and adverbs) that the examinee is able to comprehend to ensure adequate understanding of materials taught in the classroom.

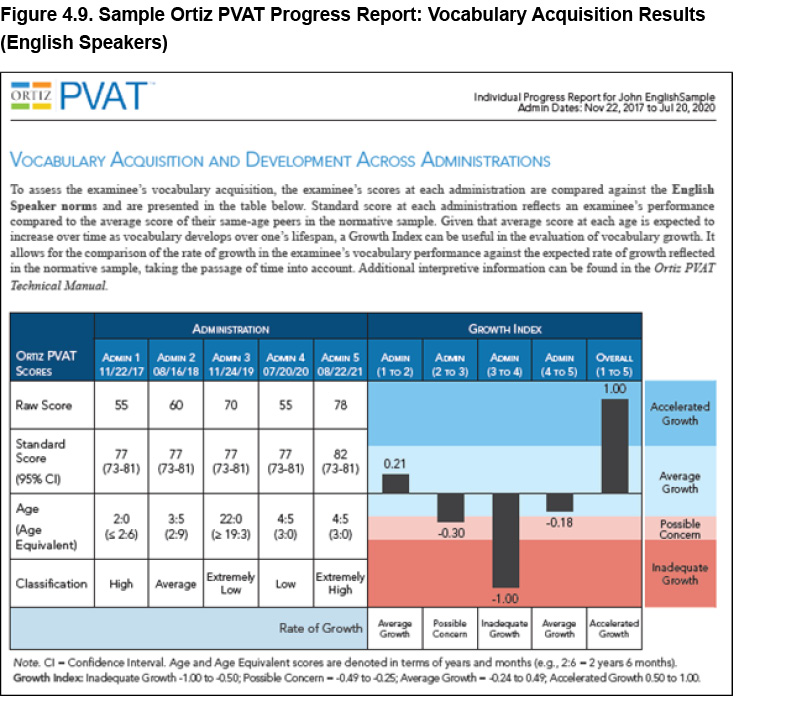

Step 5: Evaluate Change Over Time

The Ortiz PVAT Progress Report allows the evaluator to monitor and track an examinee’s progress or growth over time. The Progress Report combines results from up to five separate test administrations. Raw scores, standard scores, and age equivalent scores are included in this report, echoing information seen in the Assessment Report. A different metric for evaluating growth, the Growth Index, is unique to the Progress Report. The Growth Index indicates the rate of growth of the individual’s receptive vocabulary ability from one test administration to the next, or from the earliest administration to the most recent (see Table 4.1 earlier in this chapter for interpretation guidelines of the Growth Index). The Growth Index is found on the second page of the Progress Report, on the right side of the table of scores (see Figure 4.9 for a sample report for an English speaker).

Recall that the Growth Index is derived from changes in the age equivalent scores over time; note also that age equivalent scores account for length of exposure to English for English learners. The following section provides examples to help understand, interpret, and apply the Growth Index score.

Growth Index Example 1: Inadequate Growth. An examinee earned an age equivalent score of 13:0 at a first administration, and earned an age equivalent score of 14:0 at a second administration 23 months later. Based on these results, the Growth Index was -0.92 (Inadequate Growth). Nearly two years have elapsed, and their scores only increased by the equivalent of one year, so this examinee is demonstrating growth that is much slower than expected. Such a low Growth Index score may warrant special attention from the evaluator or intensive intervention.

Growth Index Example 2: Possible Concern. An examinee earned an age equivalent score of 11:0 at the first administration, and 12:0 at the second administration 1 year 3 ½ months later. The Growth Index was -0.30, placing the examinee in the Possible Concern range. Their scores only increased by the equivalent of one year, despite the fact that more than a year has passed between administrations. This value indicates that their scores are growing slightly slower than expected. Evaluators should interpret this range as a borderline score, as it falls close to the boundary between growth that is slightly slower than expected and growth that is within expectation. When such a result is observed, consider whether this amount of growth is concerning for the examinee and what unique factors may be contributing to the low score.

Growth Index Example 3: Average Growth. An individual earned an age equivalent score of 10:9 at first testing, and then 11:9 when tested one year later. In this instance, the Growth Index was exactly 0.00, indicating that one year of growth was observed over the course of one year. Growth in this scenario is in the expected range and this result indicates progress in line with expectations.

Growth Index Example 4: Accelerated Growth. An examinee earned an age equivalent score of 5:0, and then a score of 8:0 when tested nine months later. The equivalent of three years’ worth of growth occurred in a very short amount of time, demonstrating a truly accelerated increase in receptive vocabulary ability. Such an extreme case results in a maximum Growth Index score of 1.00, which is classified as Accelerated Growth. Note that the truncated range is implemented because such situations already represent such dramatic growth that it is not necessary to parse scores more finely.

Note that the Growth Index alone does not inform the evaluator as to whether an examinee is performing at a low or high level of receptive vocabulary acquisition; Growth Index scores can only demonstrate the rate of change over time. When interpreting these results, the evaluator should be mindful of all reported scores in conjunction with the Growth Index. For example, consider an individual who achieved an age equivalent score of 17:6 at an initial administration and 17:9 at a follow-up administration one year later. Because these administrations occurred one year apart, and less than a year of progress has been made (as the difference in age equivalent scores do not indicate the equivalent of gaining one year of ability), the Growth Index will be low and may appear to be a potential area for concern. However, if the same examinee has a chronological age of 12 years, they are still performing well above expectations and beyond what is expected of their age, despite what appears to be a small amount of growth. In this scenario, their standard score, percentile rank, and stanine would likely communicate their above-average receptive vocabulary ability, and therefore their low Growth Index score would no longer be a concern when examined alongside the other scores. Conversely, the presence of a high Growth Index value could indicate rapid progress and therefore no concern, but a below-average standard score, or an age equivalent score much younger than the examinee’s chronological age, might still warrant intervention despite the rapid growth. For example, the Growth Index could be 1.00, due to age equivalent scores of 4:0 and 6:0 at the beginning and end of one full year, respectively. In this example, two years of vocabulary acquisition (i.e., the age equivalent scores increased from the equivalent of a 4-year-old to a 6-year-old) have occurred over the course of one year, indicating Accelerated Growth. If the examinee is 10 years old, however, the accelerated growth does not compensate for an age equivalent score that is far below their chronological age.

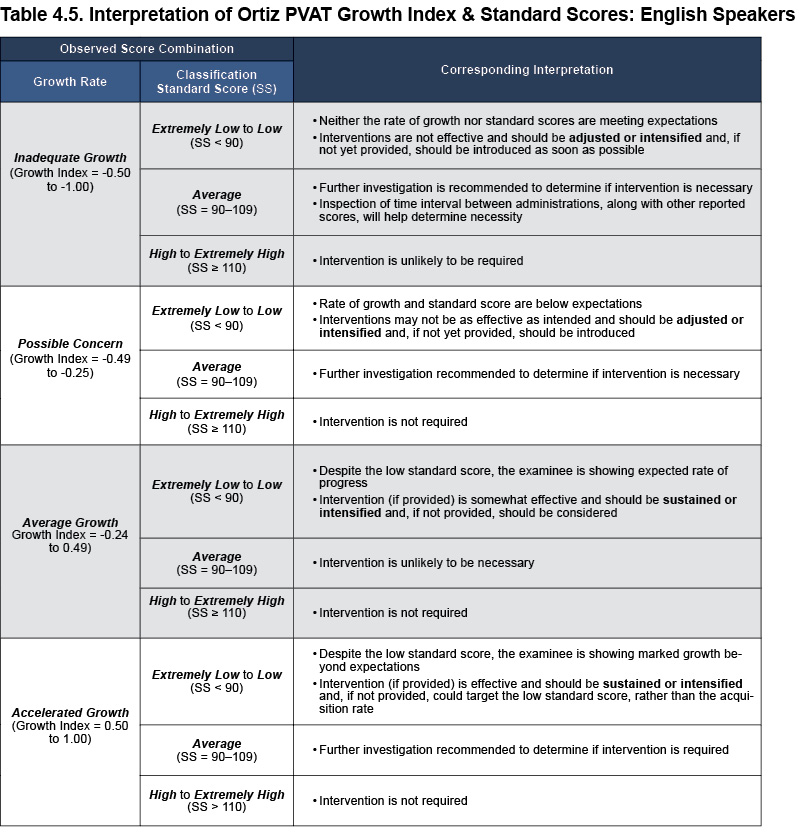

Low Growth Index scores could indicate growth that is slower than expected, or it could indicate that no growth occurred during the time interval. In such instances, it is important to consider whether the raw score changed; if the raw score did not change between administrations, then no growth occurred and the Growth Index would appear quite low. This result may not be a concern if the time interval was very short (e.g., three months), but it could indicate greater concern if the time interval is longer. Therefore, it is critical to examine how all the scores interact when interpreting Growth Index results. Table 4.5 provides interpretive guidelines for understanding various Growth Index classifications alongside different standard score classifications for English speakers (specifically, interpretation of the standard scores observed at the later administration), as well as associated intervention recommendations.

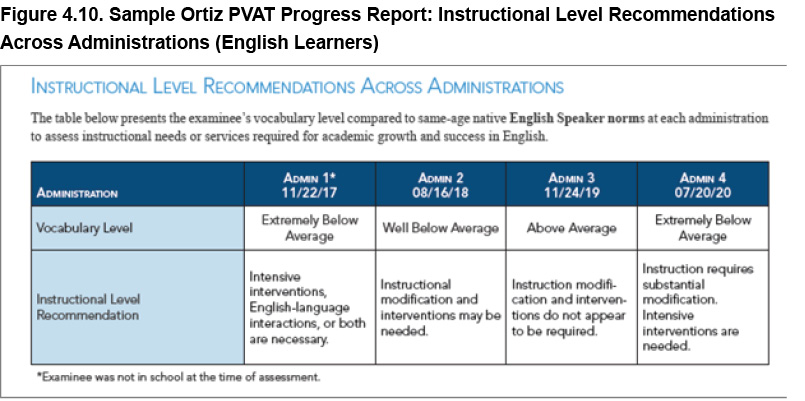

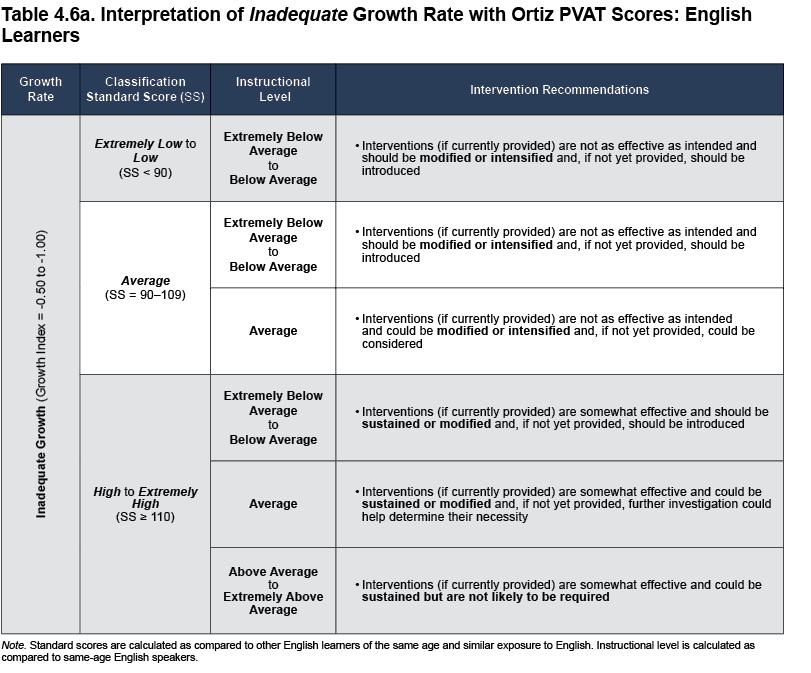

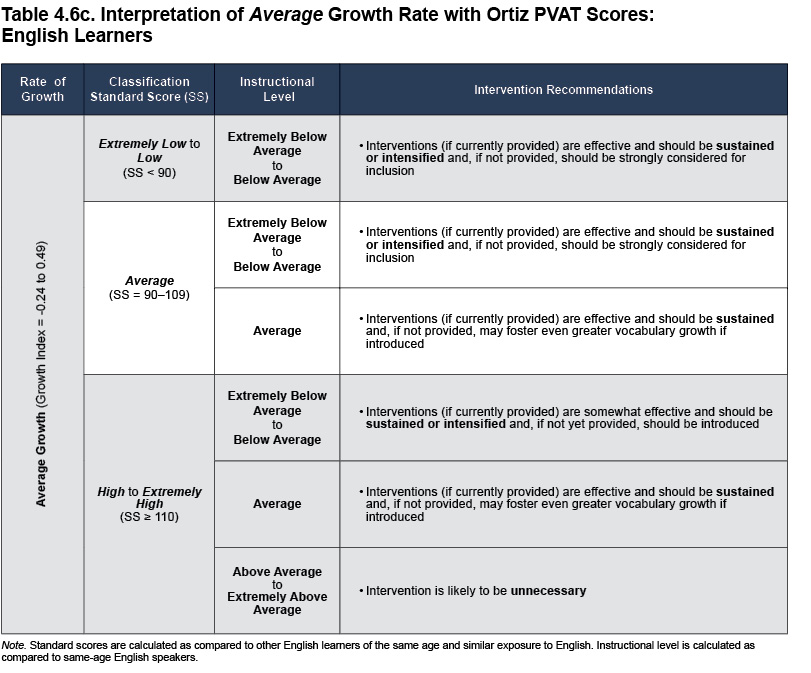

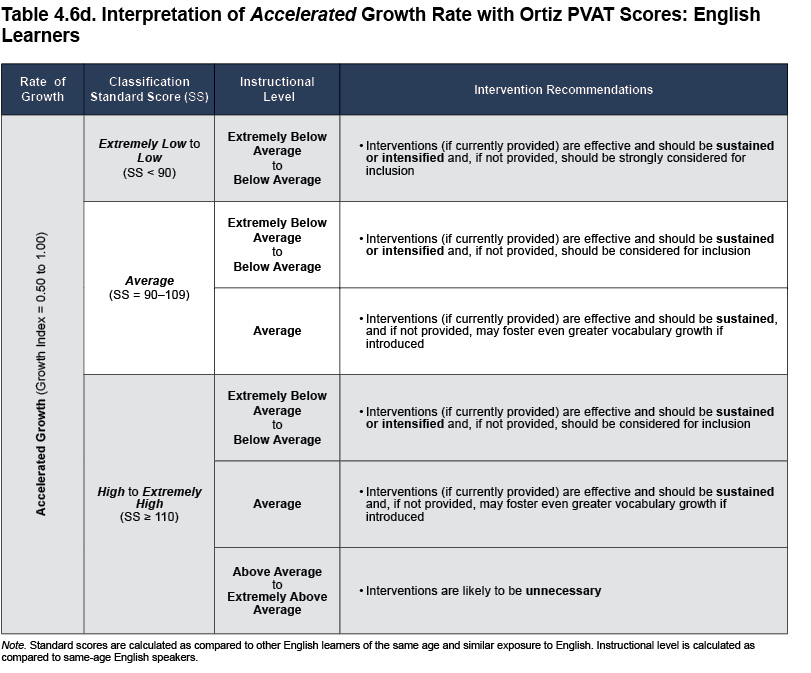

Interpretation of the Growth Index for English learners follows a similar process but with some additional considerations. English learners are initially compared to other English learners of the same age with similar exposure to English to determine possible language impairment, and they are then compared to same-age English speakers to determine instructional level (this information is found in the Instructional Level Recommendations Across Administration section of the Progress Report; see Figure 4.10). Comparisons to both peer groups are important to consider when interpreting the Growth Index, as the Growth Index alone is insufficient for determining intervention needs. For example, even an Accelerated Growth pattern may not be sufficient to elevate or advance English vocabulary acquisition for an English learner to fully compensate for being at a low instructional level relative to native English-speaking peers. Similarly, a pattern of Inadequate Growth may not be of particular concern in instances where the examinee achieves a standard score and instructional level classification in the Average range. Tables 4.6a to 4.6d summarize intervention recommendations to understand the Growth Index in association with Ortiz PVAT standard scores for English learners. Examinees who receive low scores compared to English learners, or low instructional level results compared to English speakers, may benefit from some type of intervention, and the rate of growth can be used to evaluate intervention efficacy or monitor progress. Note that not all score combinations are presented in these tables; some combinations are not possible, as the scores were designed such that an English learner’s standard score based on the English Learner norms will never exceed their standard score as computed with the English Speaker norms.

Step 6: Report Results

Depending on the evaluator’s setting (e.g., clinic, school, or private practice), different reporting formats and organizational requirements may apply. Many practitioners or school-based evaluators create written reports that include test scores, interpretation, and recommendations for action or intervention. If desired, the guidelines for interpreting standard scores (see Figure 4.1 for classification categories) may be reproduced within the report. A table format can also be used in specific types of written reports (e.g., Individualized Education Plans [IEPs]) when the Ortiz PVAT is used in public or private school settings.

| << Ortiz PVAT Score | Chapter 5: Overview >> |