- Technical Manual

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Theory and Background

- Chapter 3: Administration and Scoring

- Chapter 4: Scores and Interpretation

- Chapter 5: Case Studies

- Overview

- Case Study 1: Clinical Evaluation of an English Speaker Suspected of Having a Speech-Language Impairment

- Case Study 2: Progress Monitoring of an English Learner with Suspected Deficits in Verbal Ability and Language

- Case Study 3: Psychoeducational Evaluation of an English Learner with Suspected Specific Learning Disability

- Chapter 6: Development

- Chapter 7: Standardization

- Chapter 8: Test Standards: Reliability, Validity, and Fairness

- Task Instruction Scripts

Case Study 3: Psychoeducational Evaluation of an English Learner with Suspected Specific Learning Disability |

Bennie T. is a 9-year-old, 4th grade student of Hispanic heritage. He was referred for psychoeducational evaluation after demonstrating an array of early academic problems including difficulty with reading comprehension, math computation, and written expression.

Bennie was born in the U.S. to parents of Dominican and Mexican descent. His father emigrated from Cuba about 12 years ago, and eventually met and married his mother who had also emigrated from Mexico around the same time. The family initially settled into a rural farming community in an agricultural center near San Diego, California. Neither of Bennie’s parents had any significant formal education, although his mother had attended school on and off through the 8th grade. His father had only attended school up to about 3rd grade, after which he helped his family by selling produce he gathered on his own. He managed to save enough money to gain passage to the U.S., where he continued to work in the agricultural industry. Currently, he supervises other workers in planting and harvesting activities. Bennie’s mother works at home; she cooks, cleans, and cares for Bennie and his one older sister, who is now 10 years old and in 5th grade at the same school Bennie attends. Bennie’s family speaks almost exclusively in Spanish at home and within the community, as it consists of other families who also perform agricultural work in the same area. Bennie learned to speak English and indicates that he usually speaks English with his sister but not with his parents, as they are uncomfortable and unable to express themselves well in their accented English.

When Bennie reached the age of 3 years, he began attending a nearby preschool program that was run through the local Head Start agency. Given the demographics of the area, he was provided some support in Spanish at this time from the paraprofessionals that assisted the teachers, although the program itself was primarily conducted in English. Apart from the language difference, there were no indications of any evident learning difficulties, and Bennie subsequently entered kindergarten at the age of 5 years. He attended the public elementary school closest to his home, where his sister had started a year prior. Like his sister, he was administered the California State Exam, which is used to identify limited English speakers. Results indicated that Bennie was eligible for a special linguistic program. Although it would have been preferable, if not mandatory, that he receive some type of native language instruction, the district in which Bennie resided did not have any such English as a New Language (ENL) programs in reasonable proximity to his home. Given the family’s inability to provide Bennie with daily transportation to another school at the far side of the county, Bennie was provided the only type of program offered at his local school: traditional, pull-out English as a Second Language services.

According to teacher comments and grade reports, Bennie displayed inconsistent learning of the basic skills. For example, it took him a considerable amount of time (i.e., longer than usual) to learn the letters of the alphabet and the sounds each letter makes. This delay, however, did not seem to prevent him from being able to progress in his ability to decode words and read with a relative degree of expected fluency. His progress was evaluated by the school’s pre-referral team; it was noted that although he could demonstrate basic aspects of reading by the time he reached 3rd grade, he was continuing to have comprehension difficulties with all but the most basic of texts. This seemed somewhat inconsistent with his progress on the California English Language Development Test (CELDT; California Department of Education [CDE]; 2016), a test used to evaluate progress in English language acquisition of English learners with limited proficiency. Despite his academic struggles, he reached the highest stage (“bridging”) in 3rd grade, and this year, he was judged by the California English Language Proficiency Assessments for California (ELPAC) general performance level descriptors as also being at the highest level (Level 4, “fully functional”) in both receptive (listening and reading) and productive skills (speaking and writing). These data indicate that Bennie’s English language proficiency is at a level where the district may now legally withdraw ENL services from Bennie and allow him to receive all instruction in English without any further support. Although Bennie’s teachers concur that he seems to speak and use English quite well, they argue that his literacy is not at the grade level or in the range expected of other children of the same age and grade, including those who are English learners. In particular, as the curriculum shifted this year to focus on conceptual development, Bennie’s parents have observed that he seems to understand the ideas of metaphor and allegory and can read reasonably well, but he often cannot remember the basic content of passages he just read. Likewise, his recollection of material that he previously appeared to grasp and master remains inconsistent, which causes him significant problems during exams. Moreover, he also demonstrates difficulty with word problems in mathematics (despite his apparent proficiency in oral language) and still displays numerous minor, but important, errors in straightforward computation.

Based on the teachers’ reports and recommendations, Bennie was referred for psychoeducational evaluation to determine whether his continued learning problems might be due to the presence of a Specific Learning Disability (SLD), or if they were attributable primarily to the presence of cultural and linguistic differences. The school psychologist was called upon to conduct a comprehensive evaluation, focusing on the possible identification of a learning disability and based on the academic difficulties noted by the referring teachers in the areas of reading, writing, and mathematics. The psychologist noted that although Bennie was in the process of exiting ENL services, he was still technically identified as a student with limited English proficiency. In spite of Bennie’s apparent dominance in English over Spanish (due largely to never having received any formal instruction in his native language), as well as his personal stated preference to be tested in English, the school psychologist remained aware that there still exists a legal obligation to perform some type of native language evaluation. Also, Bennie’s release from ENL services does not change the fact that he is neither a monolingual nor a native English speaker, and that his status as an English learner should not be ignored (even after having reached the State’s mandated levels of proficiency for compliance with Title III standards).

To comply with all necessary regulatory statutes and policies, and to adhere to a best-practice approach for nondiscriminatory evaluation, the school psychologist chose to create a comprehensive evaluation that began initially with testing in English. The school psychologist reasoned correctly that in the absence of any low scores, Bennie’s performance would clearly suggest the lack of any deficits or learning problems; it would also shorten the need for any additional testing or eliminate it altogether. Of course, this reduction rarely happens, because referrals for evaluation are based on observed learning difficulties and, more often than not, at least one or more areas tested may suggest possible deficits. Identification of these areas of potential deficit would guide the evaluator during follow-up sessions that they should rely on native language testing to provide cross-linguistic confirmation of true deficits. As such, the school psychologist chose to give the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 5th Edition (WISC–V; Wechsler, 2014), which provides a measure of six of the seven most important broad abilities within the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) Theory of cognitive abilities most relevant to SLD identification within a Processing Strengths and Weaknesses (PSW) model. The one broad ability not measured by the WISC–V (i.e., Auditory Processing; Ga) was evaluated via the Ga cluster of the Woodcock-Johnson IV: Tests of Cognitive Ability (WJ IV COG; Schrank, McGrew, Mather, & Woodcock, 2014). Academic skills and knowledge were evaluated with the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, 3rd Edition (WIAT–III; Wechsler, 2009).

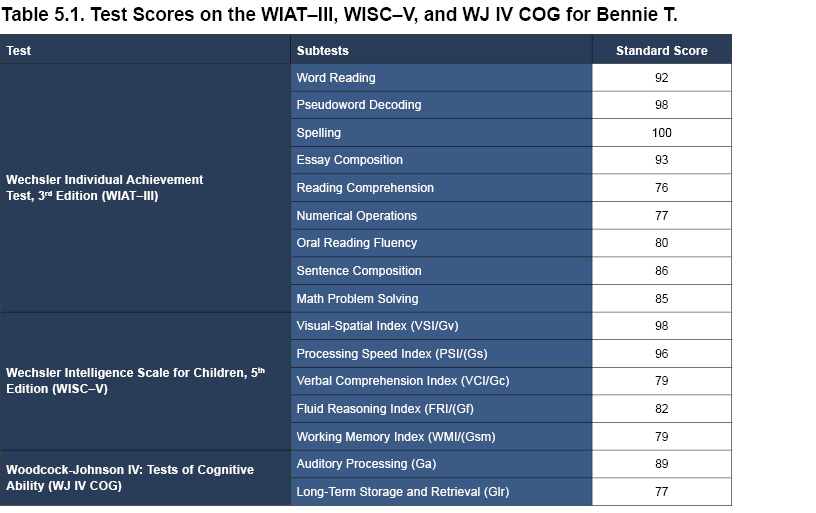

Table 5.1 presents a summary of Bennie’s test results. With respect to the measurement of Bennie’s academic skills, results from the WIAT–III were largely consistent with teacher reports and the referral concerns, and no difficulties were indicated in basic reading skills (Word Reading: SS = 92; Pseudoword Decoding: SS = 98), Spelling (SS = 100), or in writing essays (Essay Composition: SS = 93). Conversely, performance on the subtests that measured Reading Comprehension (SS = 76) and Numerical Operations (SS = 77) were well below average and were indicative of skills deficits. Bennie’s performance on tests designed to assess Oral Reading Fluency (SS = 80), Sentence Composition (SS = 86), and Math Problem Solving (SS = 85) were somewhat low but still within the low average range. This pattern of scores likely reflected difficulties in the basic aspects of reading, writing, and math that appeared to be much more problematic than what was originally suspected as these scores indicate fundamental issues with these domains. Results from the administration of the initial battery of cognitive ability tests in English also indicated areas of strength and weakness. Strengths were observed in Visual Processing (VSI/Gv; SS = 98), Processing Speed (PSI/Gs = 96), and Auditory Processing (Ga; SS = 89). Presumed weaknesses were observed in Crystallized Knowledge (VCI/Gc; SS = 79), Fluid Reasoning (FRI/Gf; SS = 82), Working Memory (WMI/Gsm; SS = 79), and Long-Term Storage and Retrieval (Glr; SS = 77).

To evaluate the degree to which Bennie’s cultural and linguistic background may have systematically and adversely influenced his performance on the tests administered, the school psychologist entered the subtest values into the Culture-Language Interpretive Matrix (C-LIM; Flanagan, Ortiz, & Alfonso, 2013). Results indicated that the observed score pattern was not primarily attributable to the influence of the potentially confounding variables of culture and language. This finding indicated that the test results were not invalidated. Also, although there was a contributory influence of cultural and linguistic factors, these factors were insufficient to prevent interpretation, assuming they could be further validated via native language evaluation. To accomplish this latter task, the school psychologist employed the assistance of a trained translator/interpreter to re-administer the tests that were given in English that were indicative of potential deficits. The school psychologist reasoned correctly that it was not necessary to retest in areas in which Bennie had already scored in the average range, as it was highly improbable that he could have achieved such a score in the absence of having at least that level of actual ability. The school psychologist faced several problems, however, that warranted re-evaluation. First, the school psychologist was not bilingual and did not speak Spanish (and had no training in bilingual evaluation), so she could not directly conduct the re-evaluation without assistance. Second, the school psychologist recognized that she might be criticized for permitting potential practice effects for re-administering the same tests, albeit in Spanish instead of English. However, the school psychologist understood the purpose of the evaluation (i.e., to identify deficits in ability that might suggest the presence of a learning disability); if Bennie could somehow demonstrate improvement via incidental exposure rather than direct teaching, it would be an indication of extrinsic problems in the classroom, not intrinsic problems in learning. Thus, any such effects of practice would be diagnostically helpful. Third, while it would have been ideal to administer the exact same tests at the time of testing, the parallel Spanish versions of the WISC–V and WJ IV were not available. As a result, the school psychologist was forced to rely on the earlier test versions that contained some, but not all, of the same tests or factor structure. Nevertheless, the best approximation to the broad ability areas was carried out, and the Spanish language tests for Gf, Glr, and Gsm were administered with the help of a translator/interpreter.

The school psychologist recognized, of course, that test translation via interpreter is not a standardized procedure and likely renders the results of the evaluation invalid. However, the purpose of this evaluation was not to establish new scores, but instead to support the validity of the prior scores obtained in English by ensuring that they were not low due to linguistic differences or other factors. Thus, the school psychologist trained the translator/interpreter to assist in observing the nature and qualitative aspects of Bennie’s responses to assist in ascertaining any detectable evidence of difficulty similar to what had been observed during testing in English. When the analysis of process and qualitative observations were correlated with the obtained numerical results, it was clear that Gf was not likely a deficit as the Spanish Gf subtests generated a composite score of 91 and there did not appear to be any perceptible difficulties during testing. Coupled with an average score in Math Problem Solving and reports from his teachers stating no apparent deficits in Bennie’s novel reasoning or problem solving tasks, Bennie’s Gf abilities were deemed to be a strength. Conversely, applying the same form of analysis to Gsm and Glr indicated continued difficulties as evidenced by the obtained scores (Glr, SS = 79; WMI/Gsm, SS = 72), as well as the observations during testing in Spanish. These findings were also consistent with the reports from Bennie’s teachers, prior observations and comments, and the results from testing in English; all data appeared to provide a link between deficits in short- and long-term memory functioning and comprehension in reading and steps for computation in math. These results provided substantial evidence for the validity of the original scores obtained via English testing of Glr and Gsm, and the results served to confirm them as possible areas of cognitive weakness and possibly supportive of the presence of SLD.

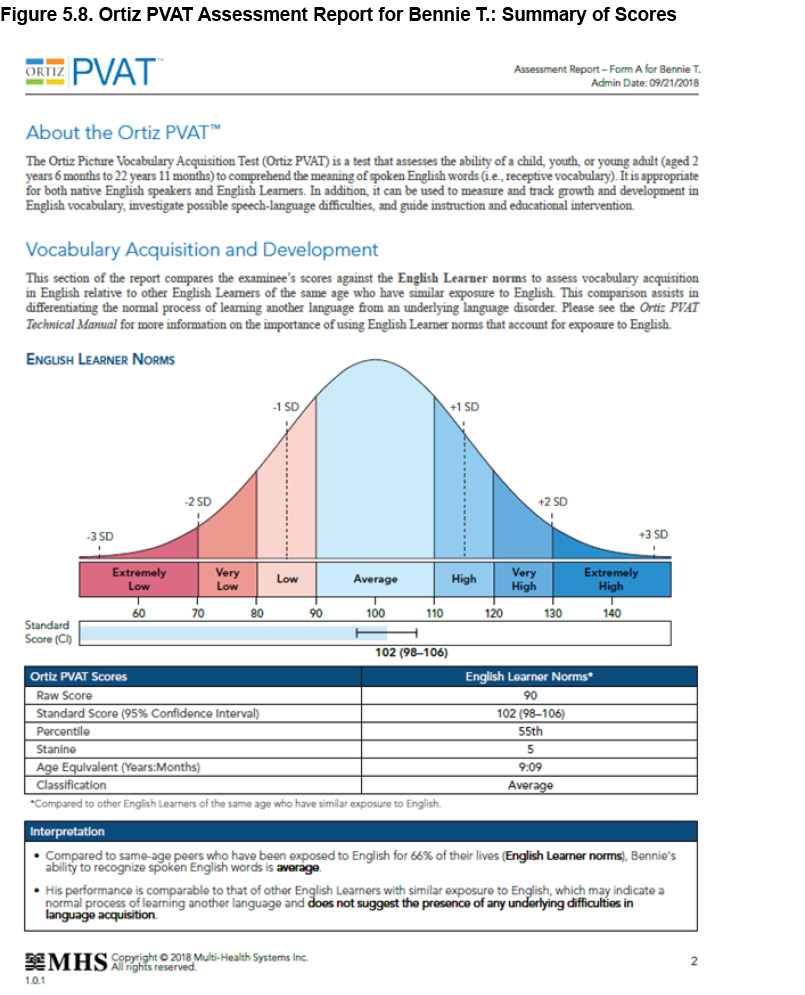

One ability area (i.e., Gc) had not yet been re-evaluated, however. The school psychologist recognized that re-testing Gc (which, in large part, refers to language) in the native language would not make much sense, given that Bennie had never received any instruction in his native language and that his parents’ educational level and socioeconomic status were unlikely to have fostered age- or grade-appropriate development in the Spanish language sufficient to demonstrate average performance in the area of Gc. Thus, he was more than likely to score in the low range, not because he lacked language ability in Spanish, but because of his linguistic and educational circumstances. Of course, the idea that Bennie’s Gc score (VCI; SS = 79) could be retained as a valid representation of his English-language ability, even after establishing the validity of his other abilities via the C-LIM, was also not likely to be true; he would be compared to native English speakers in the test’s normative sample, nearly all of whom were monolingual native English speakers—two things that Bennie was not. To address this inherent dilemma, the school psychologist administered the Ortiz PVAT. Since Bennie is not a monolingual native English speaker, the results were scored using the English Learner norms, which account for his exposure to English (66% of his life). Given the importance and relevance of Gc to academic success and the substantial contribution to general ability provided by measurement of an individual’s vocabulary, the Ortiz PVAT provided an estimate of Bennie’s Gc ability in a way that avoided the two previous obstacles. First, testing was conducted in English, not Spanish. Second, his performance in English was compared to other same-age English learners from a wide range of other linguistic backgrounds, with similar exposure to English and opportunity for learning English. Only in this way could a true peer group comparison be made that was not discriminatory and permitted the assessment of Gc ability—something that could not be accomplished properly in any other manner.

According to the Assessment Report (see Figure 5.8), Bennie obtained a standard score of 102 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 98–106. This score placed him in the 55th percentile, compared to other age-matched English learners in the normative sample who were exposed to English 66% of their lives. His age equivalent score was 9 years 9 months (accounting for his exposure to English). The results indicated that Bennie’s ability to recognize English was Average, compared to his true peer group (i.e., English learners with 66% of their lives exposed to English). As stated in the Interpretation section of the report, Bennie’s performance on the Ortiz PVAT was comparable to that of other English learners with similar exposure to English. Results pointed to a developmentally typical process of learning another language, and no underlying difficulties in language acquisition were suggested. This finding strongly suggested that Bennie’s Gc ability was, in fact, not an area of deficit, when compared to a true peer group. His Ortiz PVAT standard score clearly indicates average ability in vocabulary acquisition and should be used, not just for the purposes of describing his language ability, but also within the context of any framework for SLD.

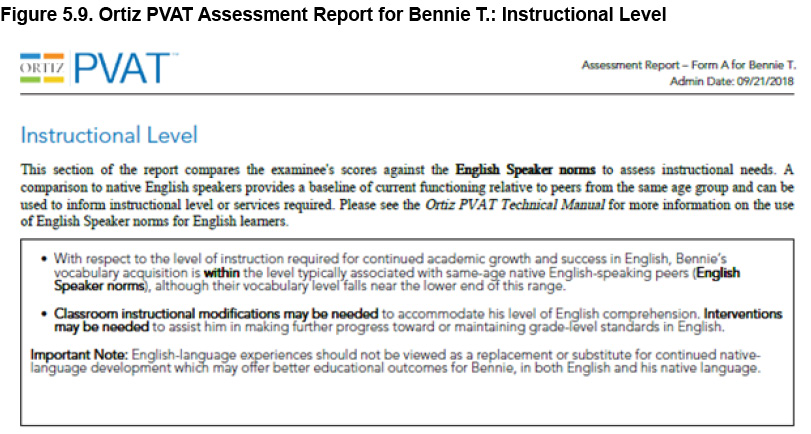

According to the Instructional Level section of the Assessment Report (see Figure 5.9), Bennie might still benefit from classroom instructional modifications and intervention, even though his level of vocabulary acquisition is within the Average range. Such modifications would be important to meet his instructional needs and to sustain academic growth and success in English. Since Bennie’s family speaks almost exclusively in Spanish at home and within the community, his native language development in Spanish would be sustained and would complement his English-language learning experiences at school and at home when communicating with his sister in English. The Assessment Report also provided some recommendations to further develop Bennie’s vocabulary growth, such as the promotion of metacognition to support Bennie’s ability to reflect on, monitor, and connect his own thinking processes. Other examples of vocabulary intervention strategies included classroom instruction based on foundational understanding of the differences between conversational and academic language and the development of deep conceptual knowledge of a word.

Armed with all the necessary information, the school psychologist used the Patterns of Strengths and Weaknesses (PSW; Flanagan, Fiorello, & Ortiz, 2010) approach to determine whether Bennie might have a learning disability. The school psychologist noted that had the original score of 79 for Gc been used in the analysis (along with deficits in Glr and Gsm), Bennie would not have been identified as having SLD due to a low overall level of general intelligence. He may well have, however, been identified as having a speech-language problem, given his Gc score in English. When the score from the Ortiz PVAT (SS = 102) was used instead of the original English language score, PSW analysis clearly indicated the presence of SLD in the areas of Glr and Gsm, as further supported by the pre-referral data. In this way, the school psychologist was able to determine that Bennie did indeed have a learning disability, and that his short- and long-term memory difficulties were causing problems in remembering (but not understanding) what he had just read. He had difficulty keeping his thoughts in logical order long enough to write a proper paragraph or essay; in math computations, he often forgot to note instances of borrowing and carrying, which led to inaccurate results despite accurately following the steps. Based on all this data, it was determined by the team that he met criteria for identification of SLD and that he required Special Education services. Moreover, the team concluded (based on Bennie’s Ortiz PVAT results and measurement of Gc) that his educational difficulties were not primarily the result of cultural or linguistic differences or limited English proficiency.

| << Case Study 2: Progress Monitoring of an English Learner with Suspected Deficits in Verbal Ability and Language | Chapter 6: Overview >> |