- Technical Manual

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Theory and Background

- Chapter 3: Administration and Scoring

- Chapter 4: Scores and Interpretation

- Chapter 5: Case Studies

- Overview

- Case Study 1: Clinical Evaluation of an English Speaker Suspected of Having a Speech-Language Impairment

- Case Study 2: Progress Monitoring of an English Learner with Suspected Deficits in Verbal Ability and Language

- Case Study 3: Psychoeducational Evaluation of an English Learner with Suspected Specific Learning Disability

- Chapter 6: Development

- Chapter 7: Standardization

- Chapter 8: Test Standards: Reliability, Validity, and Fairness

- Task Instruction Scripts

Case Study 2: Progress Monitoring of an English Learner with Suspected Deficits in Verbal Ability and Language |

Maria Q. is a 10-year-old, 5th grade student of Polish heritage. Due to concerns regarding her poor academic performance and lack of growth in English, she was placed within Tier 3 of the school’s Multi-Tiered Support System (MTSS) at the beginning of her current academic year on account of a lack of response in learning, despite attempts to intervene at Tiers 1 and 2.

Maria was born in Poland but came to the U.S. at the age of 6 where she and her family settled into an immigrant Polish community in Greenpoint, MD. Her parents had intermittent formal education and both worked daily to support the family—her father performed a variety of tasks in construction and her mother worked as a housekeeper for various families in and around the Baltimore metropolitan area. Maria has one younger sister, Evie (age 4), who was born shortly after her family came to the U.S. and has not yet started school. Maria’s family speaks almost exclusively in Polish at home and within their community, as there is considerable support for it in their neighborhood. Maria’s parents are unable to speak English in any meaningful way, but there is some emerging use of English conversational skills between Maria and her younger sister.

Although Maria was scheduled to have begun kindergarten in Poland, she was prevented from entering school there due to the circumstances of the family’s immigration status. By the time they arrived in the U.S. in February, her parents decided to wait until the new academic year before enrolling her in school. Maria subsequently entered the public school system in September of that year. She was placed in 1st grade and identified with Limited English Proficiency based on her performance on the State’s screening test that is used to identify English learners (WIDA Access for ELLs 2.0; Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System, 2009). Based on the results of the test, she was provided with English as a New Language (ENL) services; the traditional pull-out model was initially incorporated for approximately 45 minutes, five times a week, and has since decreased to only 40 minutes, twice a week. The ENL services were provided in addition to her basic instruction, which was rendered in English.

Despite the assistance that ENL services were expected to provide, Maria’s early elementary grade teachers noted difficulties in reading acquisition, written expression, and other aspects of oral language and listening comprehension. General language ability became a concern; the annual testing implemented by the State to monitor the English language acquisition of English learners indicated that Maria had progressed quickly from “entering” (Level 1) to “beginning” (Level 2) English in her first year, and then reached “developing” (Level 3) in 2nd grade and “expanding” (Level 4) by the end of 3rd grade. The school noticed, however, that she seemed to have plateaued a bit last year as she continued at the same “expanding” (Level 4) level and did not progress to the levels necessary before withdrawal of ENL services could be considered (“bridging” Level 5 and “reaching” Level 6).

Maria’s academic progress came to the attention of the school’s MTSS when universal screening at the beginning of her 4th grade year indicated that her fundamental reading and writing skills were significantly below the expected nationally-established aim lines, and that she was now in the lowest 10% of all students in her class. Following discussions by her teachers and support personnel, it was concluded that Maria had been given high-quality instruction for her first three years of school and that there did not seem to be any extrinsic reason for her apparent failure to meet the expected standards. Nevertheless, the school established a local cohort group composed of other English learners and set out to monitor Maria’s progress (particularly in language arts) from that point on. Midway through the year, the MTSS gathered sufficient results to indicate that Maria had not improved in any meaningful way and that she, in fact, now displayed four data points below the aim line. It was decided that more intensive, small-group intervention was appropriate and she was subsequently placed in the school’s Tier 2 program for the latter half of her 4th grade year.

By the end of her 4th grade year, progress monitoring data, as well as the year-end language proficiency data which indicated that she remained at “expanding” (Level 4), all continued to show that Maria was not making the same degree of progress as her local cohort peers. She remained below the established aim lines when compared to her local peers and compared to national standards. When Maria entered the current school year, she was immediately recommended for Tier 3 services so as to provide substantial one-to-one intervention at a very intensive level and to assist her in making progress toward grade-level standards. At this time, it was also decided that use of the Ortiz PVAT might provide useful information, particularly because of its ability to compare English language development not just to other English learners, but also to English learners with the same amount of exposure to English as Maria. Thus, in addition to the typical progress monitoring activities that were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the Tier 3 interventions, Maria was also alternately given one of the two versions (Form A and Form B) of the Ortiz PVAT at each of the eight-week benchmarks. Doing so helped to establish a baseline to further evaluate and examine Maria’s progress, particularly with respect to language.

Results from the progress monitoring data using tests other than the Ortiz PVAT over the course of the first half of Maria’s 5th grade year provided similar information as before: Maria was below grade level expectations and continued to display what appeared to be limited progress in all areas measured, primarily those related to reading and writing skills. Because Maria was being compared to a general local cohort group that includes other English learners in the same grade (irrespective of English proficiency), her teachers began to feel that although it might be possible that she could progress to “bridging” (Level 5), it was very unlikely and clear that she would not get to “reaching” (Level 6) and would probably remain a long-term English learner—a situation that might reflect poorly on the school and district by indicating failure to comply with the Federal Title III standards for the acquisition of English by English learners. In addition, because Maria is required to reach at least Level 5 before the withdrawal of ENL services can be considered, she was at risk for losing content instruction as she moves up to middle and junior high school. Based primarily on her apparent lack of academic progress and failure to respond to intervention even at Tier 3, the MTSS Team contemplated identifying Maria as having a language-based disability and possible placement in special education. Examination of the Ortiz PVAT data, however, provided a somewhat different perspective.

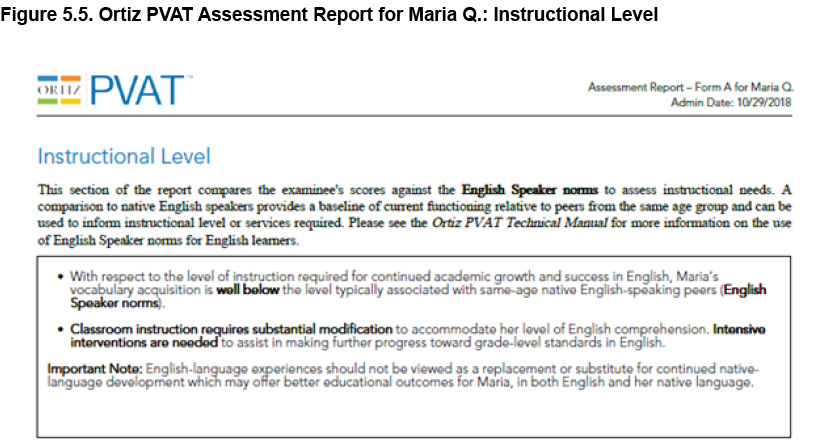

When initially administered the Ortiz PVAT, Maria’s vocabulary acquisition in English (when compared to the English Speaker norms) was very consistent with all other data; all results suggested that her current performance was well below grade level and warranted the provision of intensive interventions. Page 3 of the Ortiz PVAT Assessment Report indicated that when compared to her same-age native English-speaking peers, “Maria is well below the level of vocabulary acquisition […] Classroom instruction requires substantial modification to accommodate her level of English comprehension. Intensive interventions are needed to assist in making further progress toward grade-level standards in English” (see in Figure 5.5).

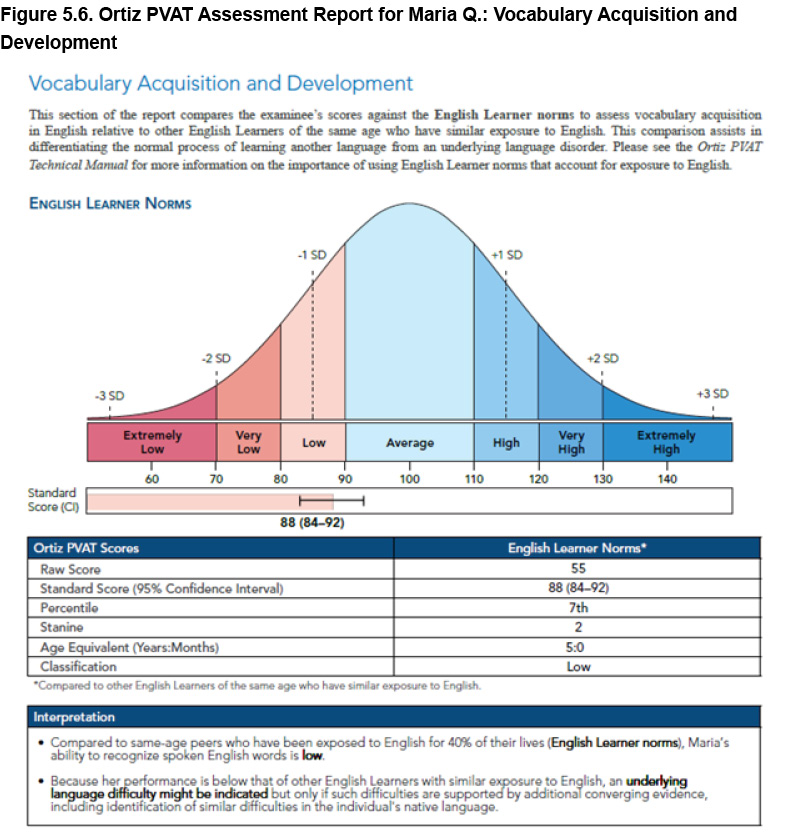

On the surface, this result seemed to support the MTSS Team’s suspicions regarding the presence of a disability. However, when Maria’s vocabulary acquisition in English was compared to other English learners with similar exposure to English, her performance resulted in a standard score of 88 (95% confidence interval = 84–92). “Compared to same-age peers who have been exposed to English for 40% of their lives (English Learner norms), Maria’s ability to recognize spoken English words is low” (see Figure 5.6). As discussed in the Ortiz PVAT Scores section of chapter 4, Scores and Interpretation, scores falling at the juncture of two categories (i.e., within two points either above or below the boundary of a classification category) may not represent a true functional difference from one category or another. The standard score and confidence interval placed Maria’s vocabulary acquisition in English as spanning the Low to Average ranges. In other words, Maria actually obtained relatively comparable results when compared to her true peers with similar exposure to or experience with English (i.e., other 10-year-old English learners who had also begun learning English at the age of 6). Such information belied the presence of a disability and necessitated further information and data prior to making any decision.

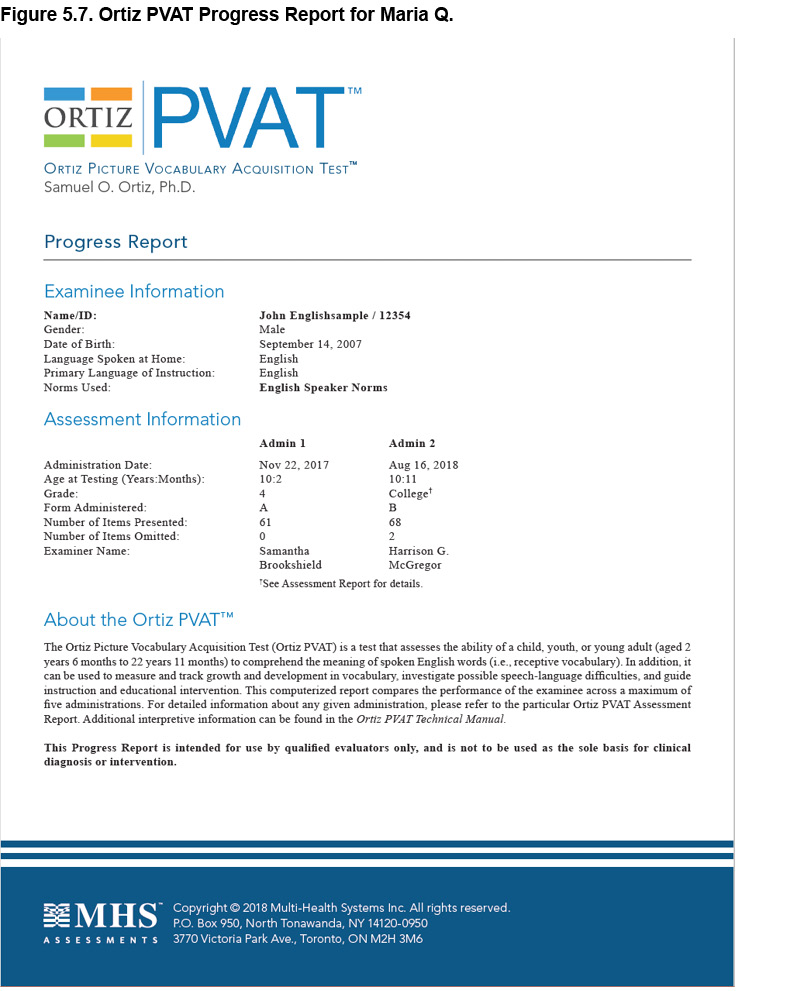

As the Tier 3 interventions continued, Maria was subsequently evaluated with the Ortiz PVAT three additional times to monitor her progress (see Figure 5.7 for Maria’s Progress Report) in order to determine current instructional needs and intervention recommendations. In each of the follow-up evaluations, Maria’s performance remained the same when compared to native English speakers. Maria did not display any increased or decreased instructional needs, and the degree of intensity in the current interventions provided at Tier 3 continued to be appropriate. Likewise, Maria’s performance on subsequent testing with the Ortiz PVAT did not vary greatly and resulted in standard scores of 89, 90, and 89. In addition, the Ortiz PVAT Progress Report provided specific comparisons of her performance from successive administrations (i.e., first to second, second to third, third to fourth, and overall). The report displayed Growth Index values of 0.25, 0.17, -0.17, and 0.25, respectively. Growth Index values between -0.24 to 0.49 indicate Average growth in terms of an examinee’s acquisition of English vocabulary (see Table 4.1 in chapter 4, Scores and Interpretation, for interpretation guidelines of the Growth Index). In Maria’s case, her Growth Index scores all pointed to growth within the expected range. These results strongly suggest that Maria was, in fact, displaying the expected rate of growth in English vocabulary acquisition (based on what would be considered average or normal for the time period between each administration, as well as her exposure to English at each administration).

Although assessment of English vocabulary acquisition by itself does not constitute a comprehensive evaluation of all language skills and areas of functioning, it does have a strong relationship to general academic success and specific attainment in reading and writing skills (e.g., Schneider & McGrew, 2012). Because the Ortiz PVAT provided a fair and nondiscriminatory comparison of Maria’s vocabulary acquisition to same-age English learners with comparable exposure to English, she was not penalized for starting to learn English at the late age of 6 years (compared to her same-age native English-speaking peers who began learning English from birth). Unlike Maria, many of her English learner peers had begun learning English at the age of 5 years when they started school (possibly sooner, due to being enrolled in preschool, having been born in the U.S., or having parents with some degree of English proficiency). Because English learners cannot be treated as a homogenous group, evaluation of performance must account for this variable; otherwise, it may inappropriately suggest or be interpreted as a lack of language ability inherent within the individual or a lack of progress when, in reality, growth and development is normal under the English learner’s unique circumstances.

The MTSS Team concluded that, in light of Maria’s Ortiz PVAT results during progress monitoring, it was highly unlikely that Maria had a language-based disability as had been previously suspected. Whereas the current intensity of intervention remained appropriate, and while the standards for expected performance continued to be based on grade level, Maria’s current inability to either learn as quickly or reach the desired standard of learning did not indicate the presence of any intrinsic deficit or lack of ability. Rather, it was determined that Maria’s unique cultural and linguistic background was a key driver of this result, rendering typical expectations of growth and learning inappropriate and unfair for someone whose first language is not English. For example, although Maria appears not to be progressing upward in terms of the WIDA Access scores, this apparent plateau is more a function of the fact that her English vocabulary suggests a low-to-average level of ability (relative to her true peers), which may simply not be high enough to meet the cut-off values for the categories that English learners are, by law, expected to reach (e.g., “bridging” or “reaching”). Likewise, while the MTSS Team appropriately implemented a local-cohort peer group standard for setting its aim lines and monitoring progress, the team did not construct this group based on English learners with differential English exposure. Thus, to prevent misidentifying Maria as having a disability or needing inappropriate placement in Special Education, the MTSS Team concluded that current services and intervention were appropriate, needed to be continued, and that she was likely a competent and capable learner (albeit, perhaps, at the lower end of the Average range overall). Consequently, Maria’s educational program remained unchanged.